The simple answer to this question is a biological one - we have sex* to ensure the continuation of our species.

This is often the accepted argument, but it falls down when we examine it. Throughout history, people have always had sex for recreation alongside procreation. Even if this were not true, the invention of the pill in the 1960s and the ensuing era of ‘free love’ almost certainly put an end to sex as solely for procreative purposes. Why then, do we have sex?

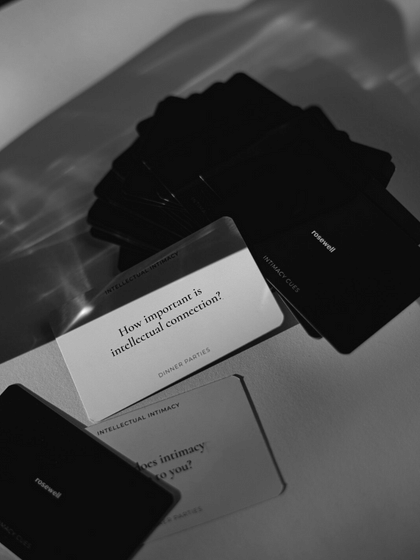

In 2008, two researchers from the University of Texas interviewed 2000 people to find out why they have sex. They received 237 answers, ranging from ‘for exercise’ to ‘getting ahead at work’, to ‘intimacy’. Very few people mentioned pregnancy. Moreover, many people continue having sex long past the age of reproduction. If sex isn’t for reproduction, what is sex for?

David Halperin in ‘What is Sex For’ (2016) points to Aristotle in Prior Analytics (4th Centure BCE) to argue that the aim of sex goes beyond the act itself. Aristotle accomplished a logical proof that:

“To be loved...is preferable to intercourse, according to the nature of erotic desire. Erotic desire, then, is more a desire for love than for intercourse. If it is most of all for that, that is also its end. Either intercourse, then, is not an end at all or it is for the sake of being loved.�?

Halperin supposes that it is possible, and “certainly romantic�? that sex aims at love (passionate, romantic love, and not non-erotic types of love). Whether this is true or not, Halperin believes the importance of Aristotle’s argument is that the aim of sex is not sex, and that the purpose of sex lies elsewhere than in modern sexuality.

Sexuality and its meaning can only be understood in its social context, according to renowned sociologist Randall Collins. Collins’ argument is that humans are fundamentally social, and our lives are a repeated set of ‘interaction rituals’ that enable and give meaning to our existence.

These rituals all involve gathering together (as two or more people), being aware of one another, attentive to a common interest, sharing strong emotion, and defining clear boundaries.

Any human social context follows these rituals - from a conversation to sexual activity. If then, meaning is derived from connection, sexual activity and sexual desire aim at connectedness.

Biological, philosophical and sociological perspectives of sex, if anything, teach us that modern sex can be complicated. Narratives in popular culture make sure of it. From all the layers of meaning we apply to sexual preference or not having sex or having too much sex, it’s easy to internalise notions of sexuality as core to our identities. At its core, sex should mean what each individual wants it to mean. But we can’t separate the individual from the culture. So what if we lived in a world where sex just doesn’t mean all that much?

*Sex is used in this article colloquially to refer to sexual activity.